In today’s world, children exist in a bubble. Practically everywhere they go and everything they do is supervised; if not a helicopter parent there is some adult within their line of sight tasked with watching over them. Rarely are kids trusted to travel even short distances alone now. Even the walk to the corner to catch the school bus typically involves an escort. Is it any wonder Millennials feel entitled? Most have spent their entire lives with a personal security detail with them whenever they leave the house.

As kids of the seventies, we were largely unsupervised, so our opportunities for fun, adventure and potentially fatal incidents were more frequent than my own daughter would encounter thirty years later. In this post I’ll share a few tales that illustrate what I’m talking about.

Stampede of Crabs

Two of Banta’s most prominent features have been removed since we lived here. One was the translucent corrugated fiberglass panels that were installed over the patios to provide some protection from the elements for any people, grills, bicycles etc. that might be sitting outside. The other was a handful of ornamental crab apple trees planted around the buildings. One summer the creative mind of a little girl brought these two things together in epic fashion.

The crab apples were a natural substitute for snowballs when you were looking for something to throw at another kid, and the trees obliged with by dropping a ready supply of ammunition down to where youngsters could reach them in the late summer. My sister was the Smart One who had all the good ideas, and I as the little brother was usually glad to play the role of the Dumb One who went along and ended up getting caught.

Gareth devised a plan where we would use discarded plastic flowerpots to collect all the crabs we could find. Next a recon mission was dispatched to seek out some unsuspecting group of adults relaxing on their patio with for a drink and a smoke (it was the 70s after all so everybody had cigarettes). With the targets acquired, execution of the plan required both good aim and precise timing. Each kid would simultaneously throw all their crab apples up on the fiberglass panels and then we would turn and run like mad, giddy with laughter.

To the unsuspecting victims, the first warning of the attack was a crash overhead, followed by an ominous shadow and rumbling sound as of five hundred little apples bounced their way over the bumpy panels. Before the adult’s brains could process what was happening, the were subjected to a bombardment by scores of tiny bruised fruits cascading over the roof’s edge. Crab apples were bouncing off heads, splashing into cold drinks and knocking the hot coal off the end of your Tareyton (whose smokers “would rather fight than switch”).

Only a mess of crushed fruit and the receding giggling of children remained.

Duobombers

Before the Unabomber and the Department of Homeland Security, fireworks were hard for little kids to access. Being good parents, our folks were careful to limit our exposure to the more benign (and inexpensive) offerings like sparklers, smoke bombs and black snakes. Had they realized my sister and I had discovered much more exciting and dangerous ways to have fun with fire they probably would have sent us to our room for a month.

Build in the 1950s, Banta had an archaic method for dealing with garbage from the residents. Behind a heavy fire door was a small stone room that contained a large incinerator. I don’t remember who lit the fire or how it was done, but several times during the week you could expect to find a good sized fire roaring inside the cast iron furnace door. The routine was that you took your paper garbage sack to the trash room (nobody used plastic bags then) and dumped the stuff that wouldn’t burn into a bunch of trash cans found in the room. Everything else was thrown into the incinerator to be burned during the next run.

My sister and I soon learned from older, more experienced miscreants that while most of the stuff the grownups sorted into the trash cans would not burn, some of it would indeed explode. So when we noticed the chimney smoking and no adults were around, we’d sneak into the trash room to search the bins for discarded aerosol cans. (This was before the world learned about the hole we were making in the ozone layer, so many consumer products came in such a can in the seventies.)

Once we lucked into the discovery of an entire raw chicken that had spoiled in someone’s fridge, affording us the opportunity to dabble in chemical warfare. While burning, it stunk up the entire complex for hours! But that was the exception; the usual munitions were aerosol cans. Firing a shot with the incinerator was a two-man mission that went like this:

One kid would hold the heavy fire door to the trash room open and act as look-out to spot any meddling grown-ups. When given the All Clear to Fire signal, the other kid would chuck all the aerosol cans we had gathered into the incinerator and slam the furnace door. Then both would make an immediate retreat as fast as possible with the heavy fire door swinging shut automatically behind.

Depending on the size of the fire that day and the nature of the ammunition loaded, you had from 10-60 seconds of running time after throwing in the cans before the explosion. A single empty Right Guard might only throw the furnace door open, while a particularly good harvest of unwanted spray paint would result in a titanic blast slamming the fire door open and belch a cloud of black smoke and ash out the chimney. Naturally this would attract the attention of every grown-up within 100 yards and put them in a somewhat grumpy mood, so we felt it was best to stay out of sight during the aftermath.

It was pretty much a miracle that nobody got hurt, especially when there was a delayed shot and you were crouched in hiding watching in horror as some innocent adult walked toward the trash room, knowing the place was going to blow any second.

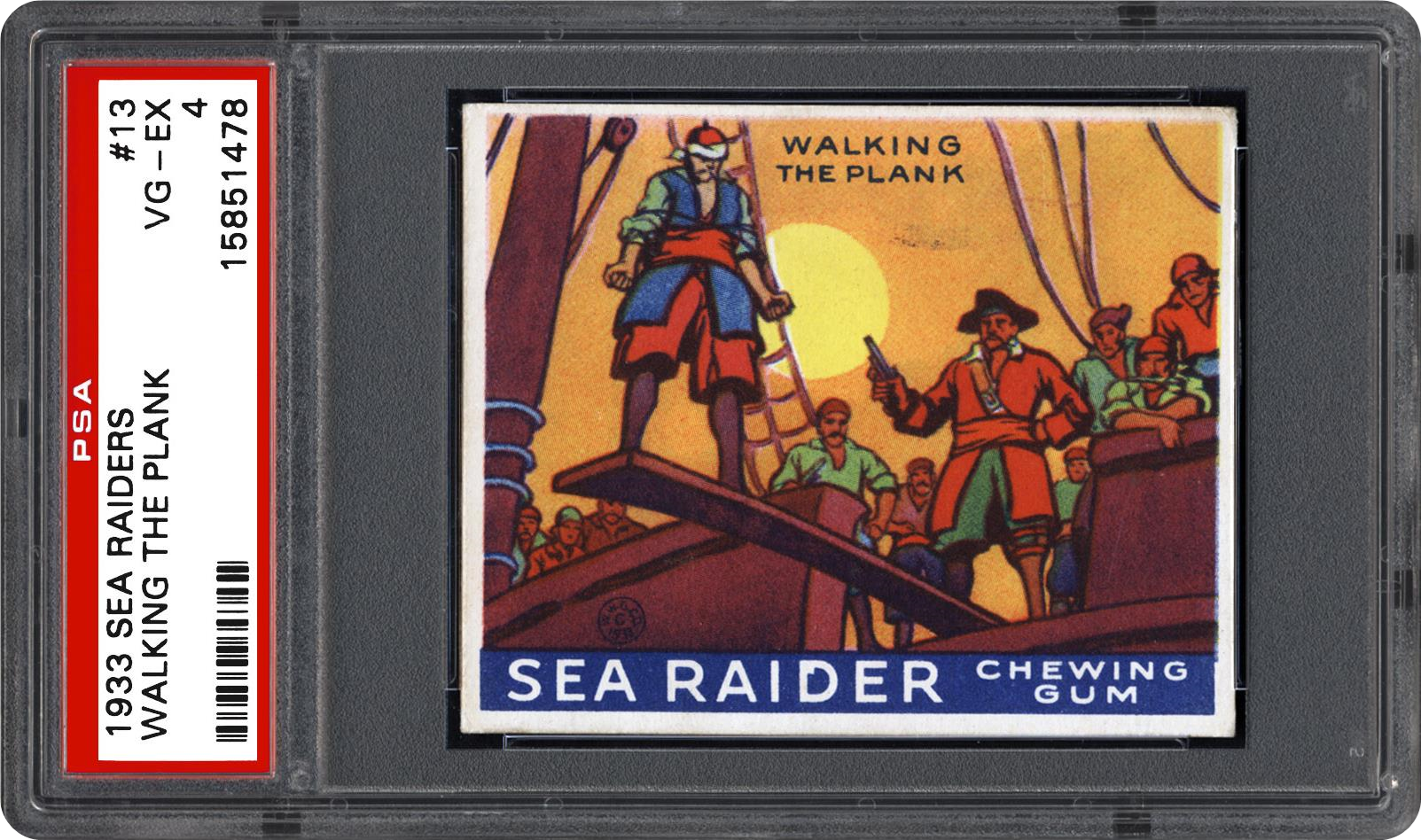

Walking the Plank / The Hanged Man

Just around the corner from the incinerator are a short flight of stairs and a rock wall. Next to that wall there is a small planting bed, and at one end of that bed a tree grew. The tree’s trunk was about twelve inches thick and the branches cleared the roof, perhaps 30 feet tall. The top of the rock wall was less than two feet from the tree trunk.

One day my sister and I were looking for trouble to get into in the trash room and we found a piece of discarded wood. This chunk of old two by eight was just the right size to bridge the gap between the rock wall and the tree. I don’t remember if it was my idea or Gareth’s, but I thought if one end of the plank was set on the top of the wall and the other end propped on the knob of a cutoff branch I could walk across the plank and get into the tree.

The similarity between this setup and the punishment plank on a pirate ship was lost on me, as was the flawed physics of the setup. The first step (fully supported by the rock wall) seemed solid enough, but as soon as I transferred more weight to the trunk end of the plank it rotated and slipped off the tree.

I rotated as I fell too, but was saved from crashing face-first into the ground below when my Sears Winner hightop tennis shoe lodged in the fork of a limb. There I was, swinging free with my hands still a foot off the ground, hanging by one foot. My glasses and the contents of my pockets littered the dirt below me. Unable to get any leverage to pull myself up with my foot firmly wedged above me and the blood rushing to my head, it became clear that I wasn’t going to escape this fix without help.

So I did what any eight-year old kid would do when I got myself in a fix – I started crying for my sister to “Go get Dad!” My sister took a hesitating step towards our apartment, then turned and said coolly:

“Not until you promise to give me all your toys first.”

Now you may tell yourself that you would resist torture, and even if placed in extreme circumstances would never give in to coercion or blackmail. But I’ll tell you what, Dear Reader, on that warm summer day in 1970 I would have sold my soul to get out of that tree, and my sister was ready to buy.

Flat Lincolns

One final tale on the topic of angels protecting fools and small children. About a half-mile from Banta as the crow flies is a cluster of shops called the Crosstown Shopping Center. Here was a small store where my parents would pick up milk, coffee, and cigarettes; sometimes my sister and I would wheedle some change to buy bubble gum or an ice cream cone.

To reach the store you didn’t have to walk on the road, but you did have to cross the railroad tracks. What does a little kid do when they have a couple of pennies left over and the cheapest candy is a nickle? Well, you put them on the track rail, of course, to be squashed into Flat Lincolns.

The trouble was the trains didn’t seem to run when you had a penny on the track, and when you came back the next day to look for your penny you could never find it again. Except for this one time…

We were heading to the Crosstown store and heard the horn of a train coming. Not wanting to miss the chance to finally recover a Flat Lincoln, we ignored the danger of a bazillion ton oncoming freight train and ran to put our pennies on the rail. Gareth being faster and wiser got her coin down and scooted off the other side of the tracks, but I was having trouble keeping mine from sliding off the curved top of the worn rail. It seemed like I was moving through molasses and was somehow unable to move with any speed as a forty car soybean train bore down on me. The engineer pulled the horn lanyard and held it, the deafening triple air horns getting closer and closer!

Right about then panic overtook me. I don’t remember what happened to my penny or how I got off the tracks. I just remember laying impossibly close to tracks in the gravel as the giant steel wheels went grinding by, flashing sparks and clacking over every rail joint with a loud clap, like a book dropped in a quiet library. I was literally scared stiff and unable to move an inch until the train was well on down the track.

Gareth came to help me up and we hustled away from there. I didn’t want anything to do with being near moving trains after that encounter. And I never found that Flat Lincoln either.